Everyone deserves to have a nice portrait of themselves- for online dating profiles, media releases, and plain and simple vanity. This includes our caterpillar friends.

A minor issue is their size – caterpillars are small. Even the biggest caterpillars I’ve seen don’t have faces larger than about 7mm. Even worse, no matter how you try to compliment them during a shoot or how good your banter is, they don’t take direction well. It’s certainly doable, but there are a couple easier options to minimize the squirming.

Some caterpillars are built to withstand freezing. The Cthenuca virginica spends its winters as a nearly full grown caterpillar tucked under last year’s plant foliage. On warm winter days, you can find them crawling across snowbanks. Occasionally they get stranded and will freeze solid as temperatures drop overnight. No worries though, when it warms up, they thaw and happily resume movement. When frozen, they are fabulously patient photographic subjects!

Our icy Ontario winters can keep many invading insects at bay but the large yellow underwing, Noctua pronuba, is a good reminder that we don’t have the monopoly on freeze-tolerant species. A European tourist, this moth also overwinters as a caterpillar and can likewise be found wandering on warmer days, and it does so without even wearing a winter coat or toque:

A frozen caterpillar is as patient as an ice cube, but don’t try this at home.

However! Most of the caterpillars we find wandering around in warmer times will not enjoy being frozen. They are not built to handle the icy life and if you tried to freeze them they will NOT have a Captain America like revival and resume fighting crime once thawed. They’d just die.

Killing off your subjects is a poor way to run a portrait studio, so it’s fortunate that the caterpillar life-style provides a less invasive method to collect some easier to photograph faces.

Caterpillars have distinct growth phases called instars, and each is marked by a shedding of the cuticle or skin. Much of the skin ends up in a crumpled mess which is sometimes then eaten by the caterpillar as a form of recycling. A caterpillar will pass no judgement if it catches you chewing your nails, so they deserve the same.

A fun fact – the face or “head capsule” of a caterpillar comes off as one intact unit:

As a consequence, I now have several little jars filled with little caterpillar faces, patiently waiting to be photographed at my leisure.

“My face! Give me back my face!” Rorschach

Key point – no caterpillars are harmed in this process, no caterpillars are decapitated, they are voluntarily defacing themselves. Just think of me as the guy rooting through your trash picking out your discarded toenail clippings. You were done with them so it shouldn’t bother you, right? And that is literally how I usually find the heads, fallen to the ground with the rest of the caterpillar waste – leaf parts, bits of shed skin, and poop, lots of poop.

Here’s a little collection of inside and outside these head capsules:

Of course a caterpillar also sheds its skin when it transforms into a pupa or a chrysalis. This head capsule of the last instar would be the largest, but in every species I’ve seen to date, it ends up splitting or breaking apart. Most of the faces I end up photographing are therefore from the penultimate instar or earlier, but here is the reasonably intact face from the same Cleft-headed Looper shown above. It’s two instars and a couple weeks between the two shed-heads. They grow up so fast:

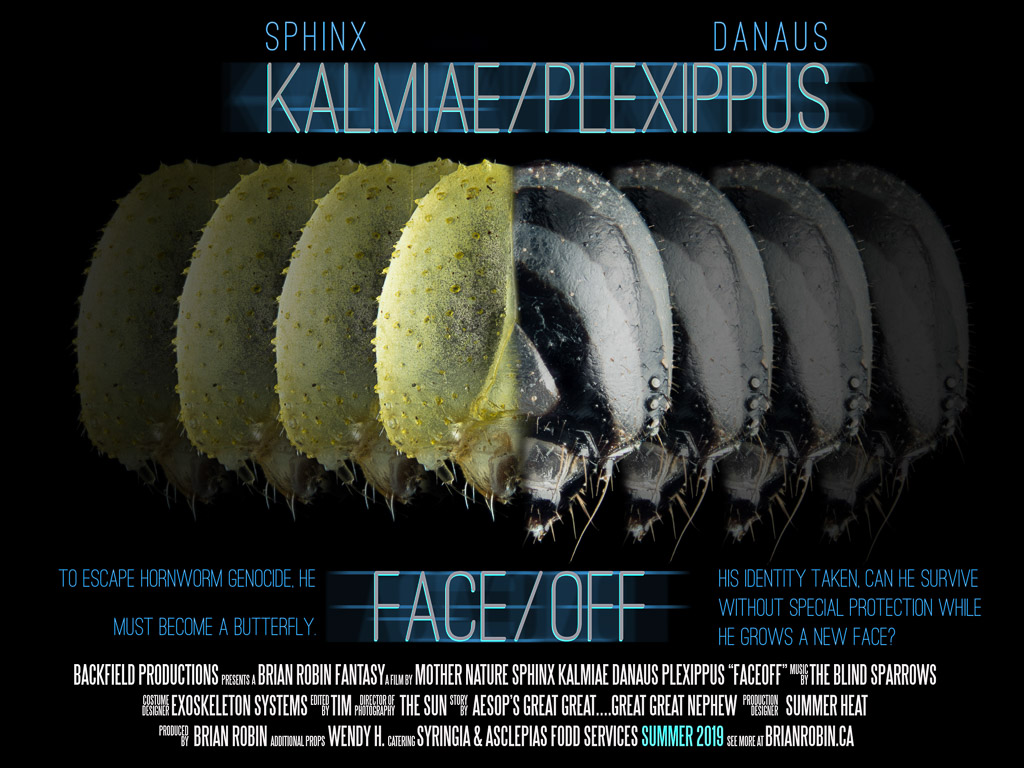

It’s been nothing but moths so far, so here’s a pair of butterflies that are very similar in their adult stages, but you’d never confuse their caterpillar phases:

H. G. Dyar – the world’s first Lepidoptera frenologist?

Dyar’s Law states that the width of the heads will increase by roughly a constant factor at each shedding, roughly multiplying by 1.5 each instar. You have to admire anyone willing to take a micrometer to caterpillar heads and note a trend. The 1890’s were a marvelous time of discovery.

This has a practical application- if you’ve got a bucket filled with a bunch of head capsules from the same species of caterpillar, you can use these big size jumps to easily sort them by instar. If you’re wondering why you’d want to sort caterpillar faces by instar, you’ve obviously got more exciting things going on in your life than I do.

I’ve taken the liberty of arranging the head capsules of some polyphemus moths according to size in a nice Space Invaders fashion:

I admit the line-up isn’t perfect. These little things are prone to static cling and exhaling at the wrong time can send them a-flying and inhaling at the wrong time can make them vanish into parts unknown. A few of the smallest heads have gone awol, but I’m not going to fret if I’ve accidentally eaten a few- they’re probably a tiny delicacy somewhere in the world.

These discarded faces (and insect parts in general) also have therapeutic value. Having photographic subjects on hand is a nice way to pass the time in winter to help stave off the shack whackies that can hit hard in February after 6 weeks with no sign of sunshine. Spend the summers collecting bits and pieces and you’ll never be bored when storm-stayed!

You can even incorporate them into your favourite board games or pastimes:

Finally, I submit an homage to Face/Off, that wonderfully cheesy John Woo action flick from the 90’s. “I’d like to take his…his face…off,” often runs through my head when looking at live caterpillars.

Possibly Pixar would like to do a remake?

Wonderful. Your talent and knowledge are inspiring to us mere mortals. Thank you for collecting the specimens and sharing the images and knowledge with us.

Fantastic! Great work, thanks Brian. Keep On! Tom at Rural Rootz.

This all absolutely blows my mind, Brian. Your work and knowledge is amazing! {And I wanted to be a real person on your web page too}